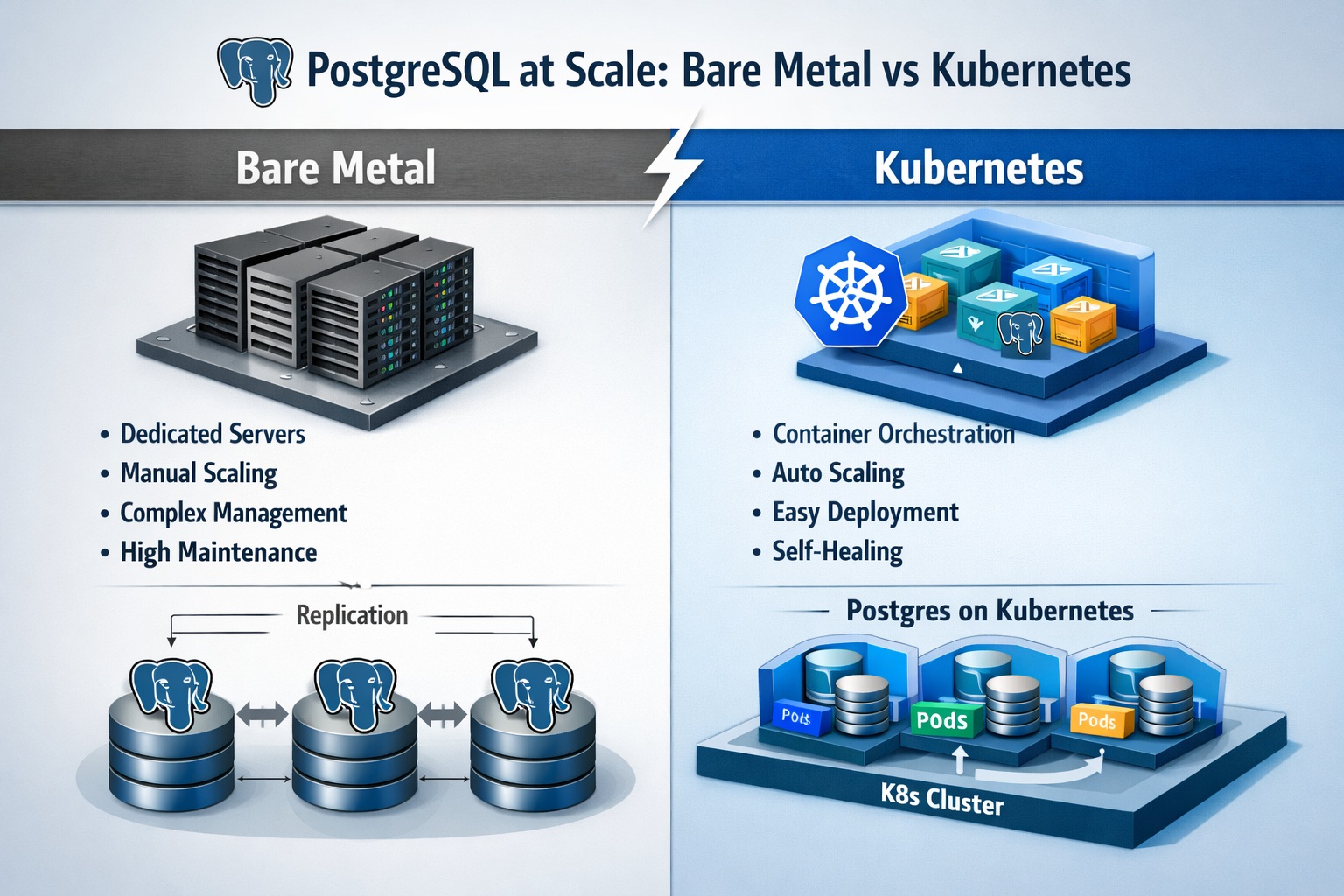

Over 18 years in infrastructure engineering, I’ve repeatedly faced the same fundamental challenge: how to run stateful systems that don’t just scale—but remain available through any failure, without data loss. When it comes to PostgreSQL, this isn’t just a deployment question. It’s an architectural one. The choice between bare metal and Kubernetes defines how you manage state, handle outages, and evolve your system over time. In this article, I’ll share my perspective—not as a vendor or a researcher, but as a practitioner who’s built and operated both models in production. We’ll compare how each approach solves high availability, updates, and horizontal scaling, and why tools like Patroni and etcd are essential on physical servers but often unnecessary in Kubernetes.

State Management: External Coordination vs Platform-Native Consensus

On bare metal, you cannot run a production PostgreSQL cluster without an external coordination layer. Period. Patroni is an excellent tool—it automates replication, failover, and config reloading—but it’s not self-sufficient. It needs a distributed consensus store like etcd, Consul, or ZooKeeper. Why? Because during a network partition, you need a reliable way to elect a new primary and prevent split-brain. Patroni writes the current leader to etcd with a TTL. If that node disappears, another takes over once the lease expires. Without etcd, there’s no source of truth—just scripts racing against time.

I’ve seen teams try to replace etcd with a simple file on shared storage or a custom script. Every single time, it failed under real load or during a simulated network partition. The “split-brain” isn’t theoretical—it’s a production incident waiting to happen. etcd isn’t overhead; it’s insurance.

Kubernetes changes this entirely. The API server becomes your consensus layer. Operators like CloudNativePG use native Kubernetes primitives: StatefulSets for stable identities, PersistentVolumes for storage, and Custom Resource Definitions (CRDs) to declare your desired state. There’s no need for a separate etcd cluster. The operator runs a reconciliation loop—it constantly compares reality with your YAML spec and corrects any drift. If the primary pod dies, the operator promotes a replica and updates internal endpoints. It’s not reactive—it’s declarative.

Some teams ask: “But isn’t the Kubernetes control plane itself built on etcd?” Yes—but you don’t manage it. You delegate consensus to the platform, which is already hardened, monitored, and backed up. That’s the key shift: from managing consensus to consuming it as a service.

Failover Architecture: Stack vs Abstraction

On bare metal, high availability is a stack of independent components. You run Patroni on every PostgreSQL node. You deploy a 3-node etcd cluster for coordination. You put HAProxy in front, using Patroni’s REST API to route traffic only to the current primary. You add Keepalived to float a VIP so clients don’t need to update connection strings during failover. This setup is stable, predictable, and gives you full control—but it’s complex. Every layer is a potential failure point that needs its own monitoring, backup, and recovery plan.

In my practice, the most common point of failure isn’t PostgreSQL—it’s etcd. A misconfigured disk I/O throttling, an unpatched CVE, or a poorly tuned snapshot interval can destabilize the entire cluster. That’s why I always treat etcd as a Tier-0 service: dedicated nodes, separate backups, strict access control.

In Kubernetes, the operator collapses this stack. You define your cluster in a single YAML file: number of replicas, storage class, backup policy. The operator handles the rest—creating pods, initializing replicas, managing replication, and orchestrating failover. There’s no VIP, no Keepalived, no external etcd. Kubernetes Services route traffic based on labels the operator updates in real time. The platform handles pod health via liveness and readiness probes. The result is dramatically simpler to operate—but you trade direct hardware control for platform abstraction.

One caveat: Kubernetes itself must be highly available. If your control plane goes down, your PostgreSQL operator can’t react to failures—even if the data plane (worker nodes) is fine. That’s why I never run single-control-plane clusters for stateful workloads.

Updates: Risky Orchestration vs Declarative Automation

Upgrading PostgreSQL on bare metal is one of the most stressful tasks you’ll do. You usually have two options. The first is pg_upgrade --link: fast, but requires two PostgreSQL versions on the same filesystem, which breaks immutability and is nearly impossible to automate safely. The second is logical replication: spin up a new cluster, sync data, cut over. It’s safer but slow—you’re copying terabytes over the network, and your app is in read-only mode for hours.

I once managed a 12 TB PostgreSQL cluster upgrade using logical replication. It took 36 hours of sync time, followed by a 45-minute cutover window. The team was on call for three days straight. One mistake in the replication slot cleanup—and we’d lose hours of data. That’s the reality of bare metal: upgrades are events, not operations.

In Kubernetes, operators turn upgrades into a declarative operation. Change the version in your CRD, apply it, and the operator orchestrates a rolling update: replicas first, then failover, then primary restart. For major versions, it can clone the entire cluster on the new version, sync via logical replication, and flip the service endpoint atomically. Downtime is seconds, not hours. The process is idempotent, observable, and fits naturally into GitOps workflows.

Moreover, Kubernetes allows safe canary testing. You can deploy a new PostgreSQL version to a single replica, run synthetic workloads against it, and only proceed if metrics look good. Try doing that on bare metal without doubling your hardware footprint.

Scaling with Citus: Same Tech, Different Realities

When replication hits its limit, Citus is my go-to for horizontal scale. It shards your data across worker nodes while preserving full SQL—JOINs, transactions, foreign keys. It’s perfect for multi-tenant SaaS (shard by tenant_id) or real-time analytics on billions of rows.

But on bare metal, Citus multiplies complexity. You now need a coordinator node and multiple workers—and each must be made highly available. That means running Patroni + etcd on the coordinator and on every worker. You’re managing a cluster of clusters, with cross-shard transactions coordinated via two-phase commit. It works, but the operational overhead is massive.

And Citus isn’t magic. Choose the wrong distribution column—like created_at for time-series data—and you’ll get hot shards that overload a single node while others sit idle. I’ve seen this bring down entire analytics platforms. Citus requires careful data modeling upfront. You must collocate related tables on the same shard to avoid cross-node JOINs, which are slow and resource-intensive.

In Kubernetes, you deploy the entire Citus topology as a single logical unit. The operator provisions coordinator and workers, configures shard distribution, and ensures self-healing. Need more capacity? Bump the replica count. Rebalance shards? Update a CRD field. The platform handles networking and storage—freeing you to focus on data modeling.

One limitation remains: Citus still doesn’t support all PostgreSQL features. Certain DDL operations, full-text search configurations, or complex extensions may behave unexpectedly in a distributed context. Always test in staging.

Cost of Ownership and Migration Strategy

Teams often underestimate the TCO of bare metal PostgreSQL. Yes, you avoid cloud licensing fees—but you pay in engineering hours. Monitoring etcd, tuning HAProxy, scripting upgrades, debugging Keepalived flaps—this isn’t “just ops.” It’s specialized, high-skill labor that’s hard to scale.

Kubernetes shifts costs from people to platform. You pay for storage, compute, and possibly operator licenses—but you gain velocity. New engineers can deploy a PostgreSQL cluster in minutes using a template, not weeks of tribal knowledge.

When migrating from bare metal to Kubernetes, I never do it in one go. I use logical replication to sync data to a new Kubernetes-based cluster while the old system runs. Then I switch reads first, validate consistency, and finally cut over writes. This minimizes risk and gives you an escape hatch.

Strategic Takeaway: Control vs Velocity

Choose bare metal if you need absolute control: direct NVMe access, custom kernel tuning, or integration with legacy monitoring stacks. It’s ideal for air-gapped environments, regulated workloads, or when every microsecond of latency matters.

Choose Kubernetes if you value team velocity, consistency, and automation. When your entire stack—from apps to databases—is managed declaratively, your mean time to recovery drops, and your on-call stress evaporates.

For new projects? I go Kubernetes-native every time. But for mission-critical, low-latency PostgreSQL clusters where I need to own the full stack? Bare metal with Patroni + etcd remains my trusted foundation.

Remember: resilience isn’t a feature you install. It’s a property you design into the architecture from day one.

← Back to Portfolio